Discover more

“I want to be an electrical engineer”

Overcoming FGM and early marriage to access education.

I vividly remember my very first attempt at milking a cow in my home in Oloirien village, Kajiado County, Kenya. I was barely 5. The sheer sight of the cow was intimidating. The smell of the fresh cow dung and urine made an already grim task even harder. As my little shaky hands slowly reached for the teats, the cow squirmed and kicked as if she was aware that I was apprehensive and inexperienced.

For a little girl, this seemed like an insurmountable feat.

Yet, the sound of my mother’s voice urging me on lifted my morale. If she believed I could do it, I definitely could. I clumsily grabbed a teat and gently squeezed. The cow gave a whimper and wagged its tail. Then little trickles of milk flowed and began to gather at the base of the cup.

I was elated.

I ran out of the shed and around our yard looking for my sisters so that I could narrate my recent achievement to them. You see, my sisters and I spend a lot of time together – washing dishes, cleaning the compound and cooking. Sometimes, we just laze around talking about our friends, our experiences of growing up and our future dreams and aspirations.

We have big dreams: I want to be an electrical engineer. And we have hope to achieve our dreams because my parents value education and insist that we have to work hard. My mother especially reinforces this fact because she never had an education and insists she would’ve loved to get an education.

Many women here are hindered by cultural practices that deter them from attaining their dreams. They don’t have a voice.

Typically, Maasai girls in Kenya are likely to undergo female genital mutilation between the ages of 11 and 13. This practice is also linked to other detrimental issues such as early, and often times arranged, marriages.

Consequently, Maasai girls are far less likely to attend school than boys. Other social issues such as the spread of HIV, high fertility rates and diminishing resources leave many families struggling to eke out a living. And because we depend heavily on pastoralism as a source of livelihood, regular famines usually turn our otherwise beautiful village into a wasteland.

It is the women and children who bear the brunt of nature’s wrath. It is commonplace to find entire villages devoid of men as they are away with their livestock in search of pasture – a venture that can lead them miles away from home lasting from weeks to months.

The women are obliged to fend for their children at a time when resources are meagre and food and water is scarce.

However, our village is gradually transforming into a cosmopolitan settlement. City dwellers are purchasing tracts of land, bringing with them influences such as drug abuse, alcoholism, insecurity and erosion of some of our traditions. People have also become more individualistic and the communal ethos diminished.

My mother tells me that growing up they had many role models. The community was a close knit unit that offered guidance and counselling to children. She says that previously, if she got into mischief or deviant behaviour, someone was likely to tell her parents if they saw her. This is not the case anymore.

That’s why many young boys and girls are succumbing to peer pressure and falling into the traps of drug and alcohol abuse.

But I’m blessed to have many advisers because I have a sponsor.

I joined my Compassion project run by the Anglican Church of Kenya in 2009. I met my teachers David, our project director, and Wilson, our social worker, who introduced me to the word of God by giving me my first Bible.

I enjoy reading and studying the word of God. It has given me a solid foundation. At the project I discovered that I could sing and dance. I am now a very active member of a youth group called “Brigade” at our local church.

David is very passionate about education and he wants us to fulfil our God-given potential in life. He says it’s difficult to find professional female role models in our community because not very many women in the past were able to get an education, which limited their potential to thrive professionally – a situation that we can change.

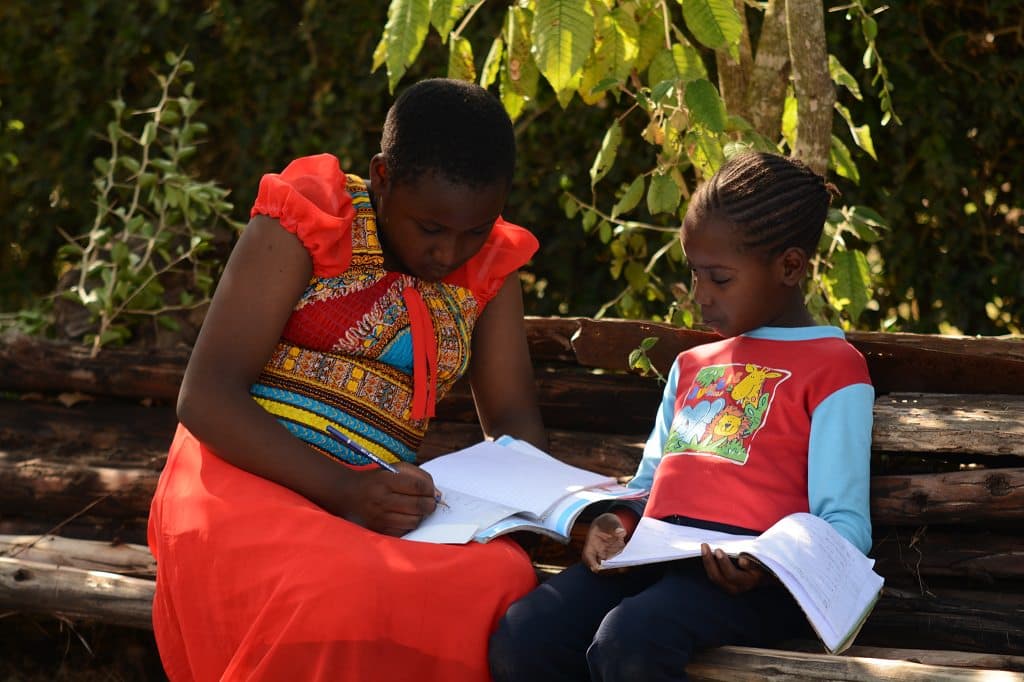

Ruth is passionate about teaching her siblings what she’s learnt at school and at her Compassion project. She regularly tutors her younger sister Helle.

They have also taught me that I can amount to anything if I put my mind to it, in spite of my background. No feat is too great.

Just like my first time milking the cow.

Knowing that all these people are on the sidelines rooting for me gives me the motivation to achieve my dreams.

That voice, like my mother’s, urges me on when I doubt my ability. It’s the constant encouragement and reassurance that every child needs.

Words by

Ruth Kipayio

Share:

Share:

Pray with us

Join thousands of people praying to end poverty, take action through our appeals and activities, and be inspired by how God is changing lives.

Get a little Compassion in your inbox with our Prayer and Stories email.

Remember, you can unsubscribe at any time. Please see our Privacy Policy for more information.